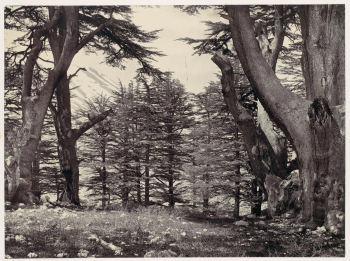

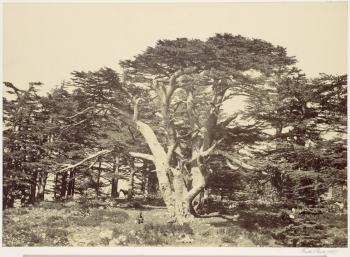

In the “Distant View of the Cedars of Lebanon” (1858) by English photographer Francis Frith (1822-98), we see the Mount Lebanon range, its peaks obscured by a fog that washes out the upper half of the black and white photograph. In the foreground, occupying half of the composition, are glaciofluvial deposits that cascade downwards right to left into an outwash plain. The deposits and the plain are the products of Pleistocene glaciation from 12,000 years ago. And at the base of the range resides a grove of trees, Cedrus libani or “Lebanese Cedar.” Known as the “Cedars of God,” this grove is one of only twelve remaining in Lebanon due to climate change. Made on one of Frith’s three trips to the Middle East, this albumen silver print is one of eleven Cedars of Lebanon within The Getty’s permanent collection. The photographs are variously titled “Distant View of the Cedars of Lebanon,” “Cedars of Lebanon,” and “The Largest of the Cedars, Mount Lebanon.” All but one is by Frith and the eleventh, taken in the 1870s, was likely made by Frith’s long-time assistant, Frank Mason Good.

Frith’s photographs of the Cedars are of renewed importance today: since the Holocene, the Cedars of Lebanon are, remarkably, migrating into cooler ecosystems found at higher elevations in search of more hospitable climactic conditions. Their migration portends their eventual disappearance when we consider their rapidly declining numbers resulting from the climate crisis. Frith’s photographs function as material witnesses: the images present a forensic scenography to global, human-made climate change in our epoch of the Anthropocene. What do 19th century photographs of biological and geological subjects tell us about climate change today? What do these photographs tell us about rising instances of migration and disappearance in the Anthropocene?

Cedrus libani are of theological, historical, political and scientific significance. Frith’s Cedars of Lebanon facilitate a reading of the intersection between these four historiographies, beginning with their textual appearance in the Books of the Bible, with Frith’s photographs and use by the British Palestinian Exploration Fund, to the Cedars’ endangered status today. These eleven photographs made in the late 19th century mark the simultaneous rise of the Industrial Revolution and the beginning of the Cedars’ decline, their subsequent migration and impending disappearance. The Cedars, up to 3,000 years old, are described in the Scriptures as “the glory of Lebanon” and are referenced in the Bible over seventy-five times. From the Phoenicians and the Egyptians, to Assyrians, Nebuchadnezzar, Romans, King David, King of Babylonia, Herod the Great, Ottoman Turks and Lebanese today, all utilized—and exploited—the Cedars as both a functional building material and fuel. Today, Cedrus libani is of significant symbolic importance to the people of Lebanon, and is depicted on the national flag, coat of arms, the national airline (Middle East Airlines), political party insignias, and as a sign of political will in the 2005 Cedar Revolution.

This project begins with the eleven photographs of the Cedars of Lebanon, as well as the significant number of print volumes, theological texts, and albums in The Getty’s collection that utilize Frith’s photographs from the Levant. These objects, I will argue, act as forensic documents that bear witness to the slow, incremental devastation wrought by climate change, yet captured within a photograph. In conjunction with 19th century forensic scientist Edmond Locard’s guiding principle that “every contact leaves a trace,” this project is an inquiry into the status of the photograph in the Anthropocene. This ongoing project considers:

a.How might the photograph, entered into a juridical arena as a legal document, act as a witness and attest to its own disappearance?

b.Can a photograph act as, or depict, a model of its erasure? How might Frith’s photos offer not simply a marker of the past, but a blueprint of future possibilities?

c.How do Frith’s photographs constitute an atemporal index of appearance and disappearance, from the first Cedars in Lebanon to their mention in the Bible; to the textual accounts of the effects of deforestation on the Cedars; to climate change in the Anthropocene and the Cedars’ subsequent migration?

d.How might photographs act as a weak sensor that has the potential to warn of impending danger, disaster, or erasure—and might this awareness or photographic sensibility require a new way of reading photographs and making images legible? And how might plant vigor provide a political sensor to conflict?

e.What do theological texts tell us about Frith’s photos? How do these texts inform both our reading of Frith’s own writings, as well as of the images today? And vice versa: how might these photographs inform Biblical scripture?

f.How might these photographs of the Cedars be understood as orientalist—and how can they be decolonized?

“The Cedars know the history of the earth better than history itself,” wrote French poet Alphonse de Lamartine—and yet the Cedars are now disappearing, threatening the erasure of this very history. This process of migration and subsequent erasure, represented by Frith’s photographs, anticipates the subsequent historical amnesia present in Lebanon after the 1975-90 Lebanese Civil War(s).

As of 2013, the Cedars of Lebanon are listed as vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. In July 2018, The New York Times published a feature titled “Climate Change Is Killing the Cedars of Lebanon,” which outlined how the biblical Cedars of Lebanon face extinction, possibly by the end of the 21st century, due to climate change. Yet the recent recognition of the effect of climate change on the Cedars was far from the first. In Edward Hull’s 1886 The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoir on the Physical Geology and Geography of Arabia Petraea, Palestine, and Adjoining Districts, we find a reference to the trees’ slow disappearance in a passage where Hull locates two causes: the first is “cosmic” and beyond one’s control. The second? Climate change due to human activity. Hull writes:

The cutting down of cedars and fir-trees in Lebanon on such a prodigious scale as described in the Book of Kings may be supposed to have been only the chief part of a very general system of disafforesting… The effect, however, on the climate could not fail to be marked.