The Right to be Seen: Archiving Absence in Post-Civil War Lebanon

Jeff O’Brien

The Right to Be Seen: Archiving Absence in Post-Civil War Lebanon, investigates the work of contemporary Lebanese artists who, after the Lebanese Civil War(s) of 1975-1990, in which 17,000 people were deemed “disappeared,” attempt to make visible these populations and their histories. In examining the work of Akram Zaatari, Emily Jacir, Jayce Salloum, Joana Hadjithomas, Khaled Hourani, Khalil Joreige, Lamia Joreige, Mohanad Yaqubi and Walid Raad, I consider how these artists attempt to produce “history” by employing similar conceptual models and visual strategies in response to questions of memory, trauma, and absence. Specifically, I ask: How does one archive the immaterial, the absent, the inaccessible after times of crisis? How does one make visible disappeared and displaced populations?

Nearly thirty years after the end of the 1975-1990 Civil War(s) in Lebanon, there still exists uncertainty as to the precise number of disappeared, let alone dead. Early post-war news reports listed upwards of 150,000 people killed during the fifteen year war. More accurate reports, which utilize a variety of sources including the Lebanese Red Cross, Lebanese Army, and an assortment of NGOs, arrive at a figure closer to 100,000 dead and around 20,000 missing. Ninety percent of the dead were civilians. These numbers illustrate a problem of representation: in conflicts with a high number of disappeared, of which the Lebanese Civil War is one of many, how does one represent and begin to account for the missing? The departed often leave few traces behind. The multitude of sectarian actors in the Lebanese conflict—in the mid 1980s close to 200 militia and sectarian groups were involved—and the subsequent rise to positions of governmental power for many former sectarian leaders makes such accounting near impossible.

La ghalib la maghlub—no victor, no vanquished—is one officially sanctioned justification for the near-absolute impunity from human rights prosecutions today in Lebanon. An amnesiac status quo ensures previous grievances will not be rehashed, in favour of a tenuous political stability. I argue that personal experiences of the war and representations of the disappeared would be nearly forgotten in official historiography, were it not for the work of visual artists in Beirut. As I discuss, the archival creations and investigations of numerous artists portray an effort to locate and uncover the archive that is often already present—is latent, or laying in wait—and requires unearthing, sometimes physical and sometimes allegorical.

The multifaceted practices of the artists I consider are sometimes mistakenly labelled as “fiction” in art historical discourse. Several of these artists, including Walid Raad and Akram Zaatari, construct alternative personas—as though the personas were truly alive—tasked with carrying out research and producing images. I argue that these archival practices can best be understood as an attempt to politically and visually represent the disappeared. I employ several of Walter Benjamin’s texts to theorize a notion of the archive that is capable of both tracing absence and accounting for the disappeared, requiring a close consideration of the relationship between the remnant, the spectral, and the archive.

There is a persistent truth about disappeared populations not only exclusive to the disappeared of Lebanon: they are both dead and alive, here and elsewhere, absent yet present. The toxic mix of legal impunity, sectarian power-sharing and historical amnesia ensures that those in power in Lebanon have little incentive to revisit the war. Crucially, this dissertation examines both how and why, in the wake of the civil war and in the face of a memory culture structured on forgetting and amnesia—where reconciliation may be impossible—it is the task of cultural producers to fill in the historical gaps and begin to write a history of the disappeared. This dissertation responds to Nicholas Mirzoeff’s notion of “the right to look,” in which for Mirzoeff, “countervisuality proper is the claim for the right to look. It is the dissensus with visuality,” and proposes a notion of counterarchiving, which I observe occurs in numerous practices in Beirut, each of offers the possibility of facilitating the right to be seen.

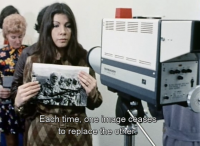

In attending to the lens-based work of these artists I consider three, non-exclusive forms of the archive: the first is spectral and latent (an archive in privation, a promissory note for the future that offers possible histories); the second is “destructive” (undertaken in the ethic of Benjamin’s “destructive character,” who attempts to “clear away” the past in the anticipation of a revolutionary future); and the third is present-absent (an archive that is either materially in ruin, stolen or missing). These counter-archives attempt to look outward with the hope of determining a possible future after the periods of internecine violence, and thereby to reimagine the continuum between the visible and invisible, evidence and testimony, documentary and fiction. By placing an emphasis on the remnant, the residual material fragment, I argue that one can begin to articulate the possibility of archiving what is absent yet spectral, and what some have referred to as an “absent present” (Mahmoud Darwish), a “latent image” (Jalal Toufic, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige), an “object in absentia” (Walid Sadek), a “night visibility” (Jacques Derrida).

Introduction: Until Proven Otherwise: Memory and the Missing in Beirut

Chapter 1: Writing After the Disaster: Spectral Archives, Latent Images

Chapter 2: A Posthumous Shock

Chapter 3: An Archive Against the Grain: Allegory and the Destructive Archive

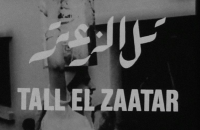

Chapter 4: The Absent Archive: the PLO in Beirut and the Palestine Film Unit

Conclusion

https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0390494